When I considered all of the places that I could set The Infinity Bridge, a range of options bounced across my brain. I wanted somewhere in the UK, but was bored with London based stuff, especially as the book is likely to have as big a USreadership as

a UK one. I think as a writer it helps to have knowledge about where you are writing about—it gives a certain integrity to the plot, and it augments the descriptive aspects of the prose.

Leeds or Manchesterwere the next considerations—I have a

good knowledge of both, having lived in one and worked in the other. But there was something missing about them, and indeed nothing that quite worked for the story. I love both cities, yet the sparkle wasn’t there.

Then it struck me... what about York? I’ve had a love

affair with York since I was a kid. My grandfather worked for the railways, based in York, and the place had attained a near mythical status by the time he passed away when I was nine. I can recall my trips there as a child to the RailwayMuseum, to the Minster, and to the

fabulous Shambles. I bought my first Charlie Brown book there, and still have the copy in the house (so... I’m a hoarder... sue me).

My experience of York as I’ve aged has been every bit as much fun. My brother, Dan, went to college there and also worked there for a while after. So I advanced from day trips to the Viking exhibition Yorvik, to pub-crawls and staying over there for weekends and even weeks at a time.

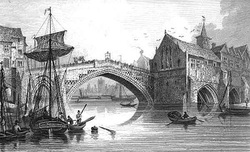

What is it about York? Quite simply it is the best historical

city I’ve every visited—above Chester, Bath, Edinburgh

Cambridge, Oxford, you name it. It wears its history

proud—and what a history. Roman walls and ruins; Vikin archaeology and exhibitions; Georgian grandeur; the Industrial Revolution; Dick Turpin, Guy Fawkes, and a thousand ghosts. It is a microcosm of British history, it bleeds it from every cobble and every sweeping frontage.

The InfinityBridge is based on the familiar concept of alternate realities, the idea that parallel to our own there are an infinite array of realities similar in many ways to our own, yet different in some specific way. What better place then to consider the divergence that could happen if, say, the Romans never invaded us? Or if steam-power persisted as the dominant technology? Or Guy Fawkes had blown up Parliament, and James I with it? For a place already replete with stories, the possibilities are endless.

So now I’d found my setting, I next needed to do

something with it. And that involved knights, androids, alternate worlds... and, of course, Merlin.

As a kid, mainly because of my love of both comics and fantasy, I adored mythology. I think the first was the Norse mythos, undoubtedly due to The Mighty Thor, with his awesome mock-Shakespeare dialogue (“I say thee nay, varlet.”). Of course the Marvel version was rather sanitised compared to the gore-laden,

head-hacking delights of the Viking tales. And from there extended the Greek and Roman, then the Egyptian—all with similar themes and ideas, although some (like the Greek) with a touch more soap-opera than the others (who wasn’t Zeus’s kid

back then?).

I always felt that the British mythology had a sort of second-best feel to it. Perhaps that is the nature of how the British legends evolved, mixing in with the range of settlers/invaders that wandered onto our green and pleasant land over the years. The legends of the UK extend from the pre-Roman days of paganism and Celtic mythology, to the Dark Ages Arthurian legends and even more modern folk heroes like Robin Hood and Dick Turpin.

It’ll come as no surprise that it’s the Arthurian legends that intrigued me the most, although Celtic tales of faeries and giants weren’t far off. The legends of Arthur have seeped so much into British culture and history that many think that they are a historical, rather than a mythical, tale. There’s so much debate about Arthur and where he arose, and whether he existed, and when, that I’ll not go into it here. Was he a Romano-British general fighting the Saxons? Was he derived as a figure from Celtic folklore? There’s great stuff to read on him, but I’m more concerned with the far more intriguing character of Merlin.

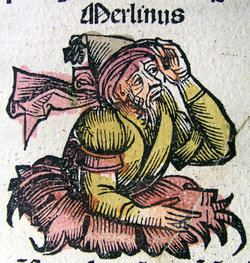

Merlin is every bit if not more fascinating than his king and friend. Merlin has never been off the radar since I was a child—whether in film, on TV, in literature. Geoffrey of Monmouth, the twelth century priest who wrote the first definitive account of King Arthur, created Merlin from a synthesis of Myrddin Willt (a legendary Welsh prophet with debatable sanity) and Ambrosius Auerilianus (a Roman-British general). Merlin was a synthesis himself, a character said to be half-demon, half-human (demon on his dad’s side, which made Father’s Day a rather memorable time each year).

And this duplicity to Merlin’s character is what has always appealed. He’s a manipulator, almost Machievellan in the way he comes across in the stories that developed since Geoffrey of Monmouth’s day. He is often portrayed as irascible, moody, intolerant of Arthur’s gallantry and chivalry.

The original (old skool) Merlin featured in several of Geoffrey of Monmouth’s works was quite fluid in nature. From the original madman concept, he moved to one where Merlin was the son of a princess and a demon, brought by the king Vortigen to sort out a tower that kept collapsing. Beneath it were two dragons, in a lake, whose scrapping kept shattering the towers foundations. These were probably symbolic of the war between Celts and Saxons (and I wonder if this featured in the idea of the dragon in the TV series Merlin). Geoffrey tweaked the Merlin character a bit more after this—the story of Merlin helping Uther Pendragon sneak into Tintagel Castle to father Arthur with Igraine (who presumably didn’t have a migraine), and the idea he was buried at Stonehenge.

Most of what we think of as typical Merlin came later,

with others moulding the character. The thirteenth century adaptation of Arthurian legend, the Vulgate cycle (or Lancelot-Grail cycle) linked the Christian themes of the Holy Grail, the love story of Lancelot and Guinevere, and expanded Merlin as an advisor and mentor of a young Arthur. It was French in origin (like Lancelot), and was later modified again to play down the Lance & Gwen naughtiness and play up the Grail-bit.

Tom Malory’s La Morte D’Arthur became the definitive version of the Arthurian legends, probably because more modern versions (like TH White’s ‘Once and Future King’ draw on it). Malory apparently started his book whilst he was locked up in prison (it beats sewing mailbags or avoiding the showers, I suppose). Merlin isn’t in this as much as you’d think, being ‘bumped off’ fairly early, but playing a pivotal sage-like role. He’s still helping old Uthor getting into Tintagel, he’s helping the young king and the sword in the stone, he’s predicting all sorts about barons and even Queen Guinevere (if only Arthur had listened). Merlin meets his end (well becomes trapped) by Nimue pretty early on, after he accompanies her away from Camelot and overseas. She dumps him under a rock, and that’s that for Merlin in Malory’s book.

TH White’s books on Arthur (The Once and Future King) threw a further spin on Merlin, depicting him as a wise old wizard bumbling through his life and experiencing time backwards (i.e. getting younger). This version of Merlin, by virtue of the Disney film Sword in the Stone, left the white bearded comical Merlin as my generation’s version of the sorcerer.

And now we have a young dark-haired Merlin, with an equally hunky Arthur, and a really odd (but compelling) version of the Arthur legend. Its ongoing popularity is a reminder that Arthurian legend is here to stay, in many media. The mature readers comic Camelot 3000 (drawn by Brian Bolland) by DC in the early 80s had an amazing futuristic vision of King Arthur, although we still have a bearded Merlin (agreeably with a suitably dark edge). So with so much Merlin in the world, who needs another version? Well, Merlin does pop up in the Infinity Bridge, but in a way which I’m certain hasn’t been seen before. And, of course, he has to have some guys to do the work for him... and they’re the (Nu) Knights of the Round Table.

And finally, and this really is a coincidence, Infinity Bridge is coming out on a new publishing cooperative label, Myrddin. The imprint carries a wide range of genres—fantasy, steampunk, paranormal romance, YA, literary fiction and even some horror. So I’ll finish with a link to the new site, which Infinity Bridge will be sitting on very very soon.... You can check it out at http://www.myrddinpublishing.com/Next time i'll be blogging about York, the setting for the Infinity Bridge....

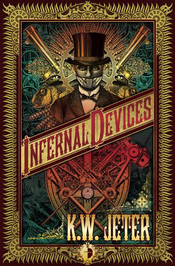

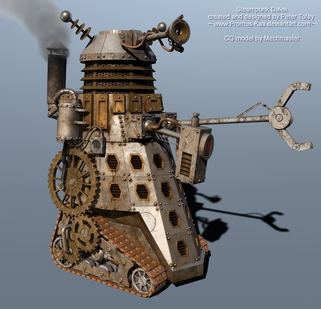

Although it features only briefly in the Infinity Bridge, the genre of Steampunk is a major aspect of the book and what I plan for the cover. One of the wonderful things about the sub-genre is the very stylish imagery associated with it. However, I do realise that not everyone has heard of steampunk, so here is a beginners guide...

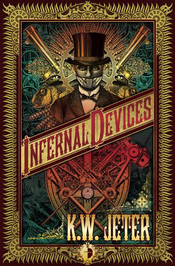

The first author to coin the phrase was KW Jeter, an American sci-fi author, who wrote a novel Infernal Devices. The book is a sci-fi/ fantasy story set in Victorian times, in which a watchmaker becomes embroiled in a bizarre story involving simulacrums, secret societies and insane inventions. The style was designed to emulate the language of the Victorian writers, like HG Wells and Dickens.

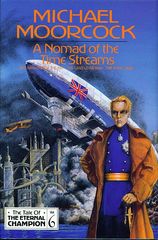

Although Jeter coined the phrase, a number of books preceded his as examples of the genre, and many have developed it since then. One of the first was Michael Moorcock, famous for his Elric books, who wrote a trilogy in the early Seventies called the Nomad of the Time Streams. This was a series about alternate realities, and an Edwardian protagonist, Oswald Bastable. The books featured airships, and steam powered machines, and a persisting British Empire. Harry Harrison, of Stainless Steel Rat and Deathworld fame, wrote A Trans-atlantic Tunnel, Hurrah! replete with steam-powered floating boats and submarines. Tim Powers, Anubis Gates, was a great Victorian time-travel fantasy which is one of the best books I’ve ever read; and Bryan Talbot’s seminal comic series, The Adventures of Luther Arkwright, has steam-punk style all over it.

In 1990, William Gibson and Bruce Sterling published The Difference Engine, in which a steam-powered computer is developed thrusting Victorian era into a premature modern age. This book was very popular, and the genre really began gaining credence at this stage.

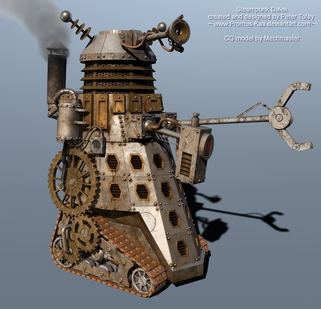

What captured the imagination is the way that Steampunk moved beyond just literature. There is a definite element of style to it: the souped up Victorian costumes; the brass fittings on everything; the clockwork; the air-ships and the steam-powered vehicles. There’s a great line in art with the genre: I especially love the Steampunk-ing of sci-fi staples such as the Star Wars characters, or Marvel superheroes like Iron Man. Its even filtered into the mainstream cinema, with Hugo released recently as an example. On my local supermarket shelves is Cassandra Clare’s Clockwork Prince series, so its seems steampunk now has mass appeal!

The chapters of the Infinity Bridge set in an alternate Victorian era were great fun to write and will feature more prominently in the next books in the series. And I make no apology if all the covers are packed with airships, clockwork robots, chaps in top hats and ladies in corsets!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed